We are pleased to release the Panopticon project logo – acknowledgement and thanks to Rikki Marr of Hawk and Mouse.

Exploring digital services we rely on which increasingly exploit our human data

We are pleased to release the Panopticon project logo – acknowledgement and thanks to Rikki Marr of Hawk and Mouse.

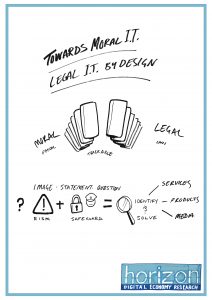

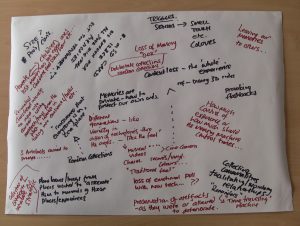

In order to reflect on impacts for wider human values and embed safeguards into technologies being introduced by Services Campaign projects, Peter and Lachlan have been holding workshops with members of Memory Machine, In My Seat and Panopticon. These workshops used the Moral-IT and Legal –IT cards developed as part of the Towards Moral-IT and Legal-IT research ongoing at Horizon Digital Economy Research.

As mentioned in the previous blog, the Legal-IT cards translate a range of data related legal frameworks into card form, from the new EU General Data Protection Regulation 2016 and Network and Information Security Regulation 2016, to the earlier Cybercrime Convention 2001. The Moral-IT cards pose difficult ethical questions clustered under the themes of privacy, security, law and ethics, such as “IDENTITIES MANAGEMENT: does your technology enable users to hold and manage multiple identities?” or “SUSTAINABILITY AND eWASTE – What effects does your technology have on the environment from creation to destruction?”. These thought provoking questions help participants to think of unexpected implications of their technology.

During a workshop, participants were asked to reflect on the technology they were building and identify an overall ‘ethical risk’ that may impact the social desirability of the technology and for its users, particularly in relation to its use of personal data. This could include the identity risks from sensitive data being compromised by poor data security practices, or personal privacy harms for individuals’ private details being made visible to unexpected parties. The groups used the Moral – IT and Legal-IT cards in a streamlined ethical impact assessment process to reflect on the overall risk, discuss and identify potential safeguards against these risks and also identify challenges of implementation of these safeguards. This activity resulted in a wide range of critical ethical questions being explored in relation to the technology with the cards and structure of the task enabling the participants to navigate the difficult ethical questions and link their technology to ethical and legal concerns more widely.

The cards were also used as part of workshop run by Lachlan and Martin Flintham, as part of their Digital Research funded project, to generate thought and encourage discussion about ethical implications of using the ‘Internet of Things’ in both the university and research environment.

We were pleased with how the participants took to the cards. They enjoyed using them and found them helpful in exploring and engaging with the ethical and legal issues in relation to their technology. They were received well, with their utility in structuring debate around complex topics. However, they also brought the wide range of issues to the fore. We are therefore encouraged that the cards have the potential to be a particularly useful tool in enabling technology developers and users to reflect on and navigate the complex ethics of their technology and produce more socially desirable technology as a result.

If you would like to know more, the Moral-IT and Legal-IT cards, and an outline of a way to use them, are now available to download online from ‘Experience Horizon’– a website which provides opportunities to try out some of the outputs from projects conducted at Horizon Digital Economy Research. If you do choose to investigate them further, we would really like to build up dialogue on who you are, how you are using the cards, why and any feedback you have on the tool/process. Please send these on to lachlan.urquhart@gmail.com.

Members of the Privacy, Law and Ethics Cross Cutting Theme are planning analysis and preparing a paper to submit to the Journal of Responsible Innovation, towards the end of the year.

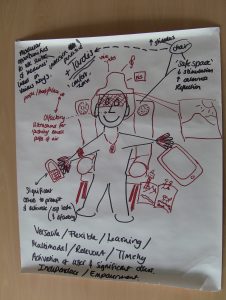

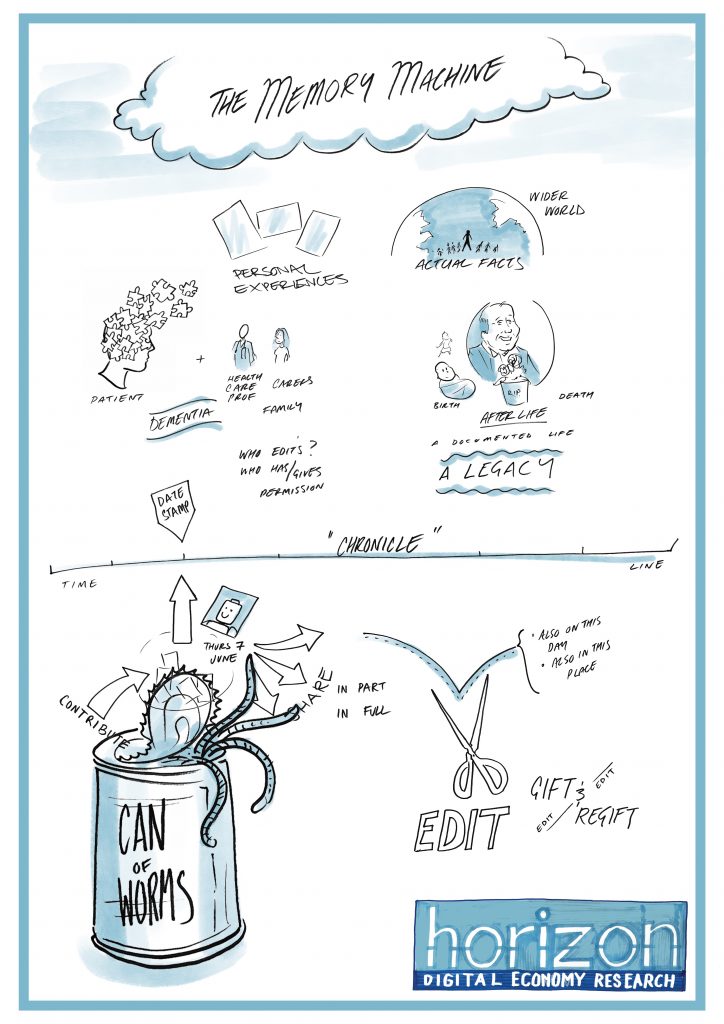

Finally, following a presentation of the project, the Privacy, Law and Ethics Cross Cutting Theme project has been neatly summed up in a visual form as can be seen below – our thanks and acknowledgment to Rikki Marr of HAWK&MOUSE.

Written by: Lachlan Urquhart and Peter Craigon

For the entirety of my adult life, I’ve been studying culture, based on the conviction that media products (however ‘mindless’ and ‘disposable’ many claim them to be) play an incredibly valuable role in all our lives. This is because they are bound up inextricably in our wider experiences of the world, of other people, and in our emotional reality.

It’s easy to identify moments from my own life that illustrate this point. Anaesthetising my teenage anxiety, while I waited to hear if I’d got my University place, by concentrating instead on the characters in a favourite book, Annie Proulx’s The Shipping News. Escaping to Middle Earth after my PhD examination by watching the Lord of the Rings Trilogy (extended editions) back-to-back. Euphorically dancing around the flat with my newborn daughter to Paolo Nutini’s Pencil Full of Lead singing “best of all, I got my baby”.

These formative experiences that stick in my memory are linked to and enriched by the media I consumed in those moments. And perhaps the stickiness of those memories is reinforced every time I encounter that content again. Certainly particular pieces of media trigger particular memories, and that nostalgia can be quite visceral. For example, Beyoncé’s Crazy in Love reimmerses me in another swelteringly hot summer – 2003 – when that hit single seemed to be continuously blasting through the open windows of every vehicle in London.

Lots of amazing, imaginative work is being done to take advantage of the propensity of media to ‘transport us’ in time and space, especially when memories and/or media become harder to access. The WAYBACK is a virtual reality film, funded by £35,000 pledged to a Kickstarter campaign, that recreates Coronation Day 1953 to help those living with Alzheimer’s and their carers recall the conversations, music and atmosphere of a street party. In situations when people’s cultural worlds become restricted, digital apps can also help maintain access to content and all its benefits. Armchair Gallery is developing an app to enable digital access to, and creative interaction with, artworks in collections for those who cannot physically visit them.

What excites me about the Memory Machine idea is imagining an in-home media repository cum player that could automatically connect personally important content (e.g. a pop song) with a period of time (e.g. when you added it to your music collection or listened to it a lot) and with other contemporaneous media (e.g. a film or advert of the time that featured the song). This has the potential to generate multi-layered, multimedia connections between individual and historical context. More than that, a system that could link one person’s cultural experiences with those of people around them would also transcend the artificial limitations we all apply to media on the basis of personal taste. I think it would be wonderful if my daughter could one day, as an adult, get a sense of the love and joy she brings me by being played a pop song from ‘before her time’.

Written by Dr Sarah Martindale

We are creating a digital experience which will make your bus journey more enjoyable and more interesting by linking you to various types of content, including local information, mini-games, and user-generated content, through your specific seat or vehicle.

You are invited to take part in a workshop on Wednesday 15th August at 2pm, taking place in A19 of the Nottingham Geospatial Building on Jubilee Campus, University of Nottingham. The workshop will last approximately 1 and a half hours.

The aim of the workshop is to interact with, refine, and feedback on paper prototypes and mock-ups of the service which will then feed into the development of the app.

We are particularly interested in

This will involve paper-based activities and discussion, and you will be thanked for your time with a £10 high street/Amazon voucher.

For more information, and to sign up for the workshop, please email Dr Liz Dowthwaite

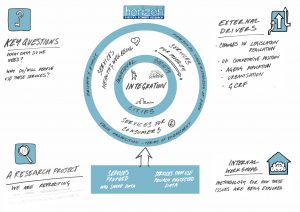

The Horizon ‘Services Campaign’ was recently introduced to a few of our CDT students at an event aiming to bring together academics, researchers and administrators with shared interests, and to identify additional current projects exploring services, and how they might take on increasingly experimental qualities through deeper connections to the physical world or to digital media.

Rikki Marr, creative and live illustration agent and founder Director of HAWK&MOUSE attended the event and helped bring the Horizon ‘Services Campaign’ to life through his rapid drawing, resulting in our fabulous new logo:

Illustrations for Service Campaign projects, both Cross Cutting Themes and Chronicle were also designed by Rikki and we will be unveiling them all shortly.

Written by: Hazel Sayers

This was a presentation I gave internally to the Horizon research team on the development of the Chronicle platform. Of course it’s missing the audio but I’ve attempted to annotate the slides with enough information to give a flavour of the meaning.

Links

Dominic Price, Research Fellow, Horizon Digital Economy Research

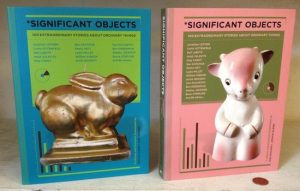

Material objects are undoubtedly powerful conveyors of memory. We need not search too far to find compelling evidence of this phenomenon. Whether personal keepsakes and mementos, or social and cultural artefacts, material objects by their simple presence can trigger, elicit and evoke feelings, associations and memories.

The nature of such objects can be a quite complex picture. On the one hand, there are objects that from the moment on their mental conception are ‘destined’ to become Things of import and notice. For example the Parthenon temple was designed to be a statement, a cultural monument, while the first drawing handed to you by your nephew is going to forever be treasured. On the other hand many objects that are normally unnoticed, or even quite mundane, may suddenly become elevated from mere objects into notable Things of Significance simply by some act, event or association. An ordinary mug gifted by a loved one may forever be cherished and used daily, while the otherwise normal THF134576 bus[1], which Rosa parks refused to give up her seat in, is nowadays found on display as a historical artefact and icon for an entire movement. Essentially they become Meaningful.

With the above in mind it can be understood that material objects have an ‘existence’ of their own. Being tangible they exist in space and time, and through interactions with people and other objects they can become Things, and more pertinently, can acquire a Record of sorts. On the more ephemeral side, it can be imagined that any object that we interact with in some way, leaves a footprint in our memories: we observe and maybe touch them; we remember facts and stories about them; and sometimes we recount and communicate these stories to others. Sometimes we make detailed documentation and likenesses of them, in writing and in art. Thus these things begin to gain a Record which can serve both as a way of sharing them within and beyond their actual physical existence.

Such records are valuable and often crucial in reconstructing the meaning of things outside of the limitations of oral history. And between the prevalence of museums and cultural heritage organisations, and the popularity of things such as eBay the Antiques Roadshow, it is also reasonable that such Records are often found fascinating by wider – and also very specific[2] – audiences. A very telling example demonstrating this phenomenon was the Significant Objects project[3]. The way they achieved this was to first procure several seemingly worthless objects from auctions and flea markets. They then got authors to endow each object with a detailed fictional backstory and proceeded to place them up for auction on eBay. Just by giving a ‘story’ to these objects their perceived value increased dramatically and they were all auctioned off at values vastly larger than their original purchase price. The intangible sense of Meaning or even Identity that these objects where artificially given was a strong enough catalyst to change each from ordinary clutter to extraordinary artefacts of meaning.

So how does all this relate to the Memory Machine and Mixed Reality Objects? Well, part of the answer lies with the increasingly prevalent Digital Records. The Digital Information age we currently live in revolves around the rapid creation and dissemination of information. Compared with just a few decades ago, the rate by which we can create and consume digital information has increased astronomically, and shows no signs of slowing down. Now this has in itself introduced new and very complex questions and issues, which are going to occupy researchers for the considerable future, but it has also given us more powerful and varied ways of recording and sharing information about the things we care about – and seemingly making that information ‘perfectly everlasting’. For an obvious example, we can now so easily shoot super high resolution pictures, videos and audio of our families, friends, possessions and experiences at any time, off the smallest, most convenient and pervasive devices that reside in our pockets. We can save, duplicate and share that content with anyone around the world instantly. And we can keep doing it non-stop, whether prudent or not.

Just this case has so very many short and long term, direct and knock-on, effects for our personal and social lives. These digital records will never fade. Good or bad, they are here to stay. We in effect can achieve ‘perfect’ recollection, dare I say we could possibly experience ‘total recall’. The faces in the photographs will not fade. The voices in the video and audio recordings will not wear out and become scratchy echoes. We currently may have only had a couple of posed sepia photographs of our great grandparents, which have faded from their original blurry – almost airbrushed – quality. Those few fragments of memory conveyed just enough uncertainty and mystery to excite our imaginations. It will not be the same for the next generations. The children of our children will not have to wonder what we looked and sounded like. They will find out, through the thousands of 4K HD videos that we posted on social media in a narcissism driven need to project and immortalise our ideal selves.

And the same applies to our ‘Things’. Every time we tweet a picture from our road trip, with our family car in the background, we are essentially creating a ‘Digital Footprint’ – in the form of that picture and tweet text – that relates to that particular car. Every time its number plate gets registered somewhere a trace is created. Every time we take that car for an MOT we create a footprint in the form of a certificate and a receipt. We keep these things for different reasons, but we can use all of them to reconstruct a detailed history of that car. What it was, where it was, how we used it, and what it meant to us. And conversely, it can do the same for us, acting as stimuli that remind us of past experiences.

Further complicating this picture, we have technology driven phenomena such as the Internet of Things, which encompass the idea of embedding technology into objects and the environment, most of which in one way or the other create even more data and information about that object and its owners. So now we have cars with on-board sensors such as GPS, tracking everything the vehicle does, for ourselves, our mechanics, and more sinisterly, our insurance brokers.

So between the stories we create and keep about them, and the traces that are captured automatically though pervasive technology, the objects around us are now acquiring ever increasing Digital Records about themselves and us. Several questions should therefore be asked: Is this reasonable? Is it practical? Is it worth it? Is it sustainable? Is it safe?

The answers to most of these questions are going to be – as with most things – somewhere in the middle. It can be strongly argued that digital records are a reality that we have to now deal with. Even if one was to never personally record any such information themselves, other people, systems and environments would most possibly capture traces of them.

Thus awareness and the ability to manage and regulate your information – and that of your objects and environment – becomes a necessity.

Furthermore it bears keeping in mind that the paradigms that we currently have in mind about what can constitute the footprints in a Record will also change. The current obvious examples of text, images, video and audio are defiantly powerful types of content for a Record. But increasingly there are other forms. Vast quantities of data can be aggregated and made sense of and tell stories of our behaviour. Snippets of information that we would normally discount, such as the use of rail and payment cards, location data from our phones, our monthly utility bills and shopping lists can all be used to identity and reconstruct patterns of behaviour with astounding accuracy (or baffling inaccuracy). In addition new forms of imaging technology might very well surpass what we concretely consider as a visual footprint. 3D scanning is becoming an increasingly able and affordable technology that can be used straight off our phones. So what happens when instead of pictures of our children, we have 3D scans of them? What happens when we can then experience those captures in virtual and augmented reality? When we can 3D print copies of cherished things at will, or as has already been attempted, bring them back to life as holograms… ?

So we introduce the idea of Mixed Reality Things – that is objects and identities that can exist in both the material and the digital realms, consisting of the amalgamation of their Records and can be experienced through several different mediums. They are persistent and can effectively and powerfully convey memories and experiences, evoking the feelings, reactions and wonder. The Memory machine can draw upon this concept to and the discourse above attempts to demonstrate that deep consideration must be given when drawing the concepts and goals of the project. We see how both stories and objects are powerful effectors for memory, with one bringing about the other and vice versa. We must consider how stories can be elicited and told around objects. And we must account for the fact that objects can trigger and enable storytelling. Thus to serve its function, the Memory Machine must be able to accommodate these facets.

In the Memory Machine workshops both cases have surfaced, with participants pursuing ways of capturing stories and experiences inside material artefacts, and conversely examining ways of ‘immortalising’ the form and likeness of objects through captures such as images and even 3D scanning and virtual reality, thus enabling new ways of experiencing them.

Projects such as Mixed Reality Storytelling[4], and the Armchair Gallery[5] have employed such capture and dissemination techniques, and they could be incorporated into the Memory Machine as well, while also enabling the ability to carefully manage the content by retaining control of the authorship and access of the data through platforms such as Chronicle.

Dr Dimitrios Darzentas

Find out more at www.MixedRealityStorytelling.net

[1] https://www.thehenryford.org/collections-and-research/digital-collections/artifact/316872/

[2] https://www.atlasobscura.com/lists/the-ultimate-list-of-wonderfully-specific-museums

[3] http://significantobjects.com/

[4] http://www.mixedrealitystorytelling.net/

[5] http://imaginearts.org.uk/programme/armchair-gallery/

Researchers at Nottingham University would like to invite you to the second Memory Machine workshop, as part of a series of workshops (4 in total) that explore how new technologies can help us preserve memories that are important for us.

The workshops will be led by artist Rachel Jacobs and privacy and ethics expert Lachlan Urquhart. These will be interactive and creative and we welcome older adults, those caring for people with early onset dementia, historians and tech developers.

Participants will receive a £10 and travel expenses to the venue covered and it includes lunch and refreshments.

The workshops will take place at the Institute of Mental Health. Everyone welcome. The venue is wheelchair accessible. Please email Rachel Jacobs to discuss any access requirements.

Please register to attend here

The Panopticon project is developing a system for measuring how visitors to the National Videogame Arcade in Nottingham engage with the various wild and wonderful games that they exhibit in that space. We’ve taken the name from the infamous prison design where occupants were watched at all times by a single guard, however the modern twist is to involve the visitors to the NVA in a meaningful conversation and decision about what’s done with the data they generate.

We’ve spent the first couple of months thinking about and beginning to develop our engagement tracking system. This is a computer vision based system that, using cameras mounted on various games in the NVA, will watch and measure how engaged players are. That’s more complicated than it sounds. Firstly, the NVA has lots of different kinds of game and exhibits that players and visitors can explore. We did an initial site visit with Exhibition Manager Alex, and came to the conclusion that we want to experiment with tracking engagement with three different kinds of exhibit:

The variety here leads to some challenges for how we can measure engagement. The technology we’re developing is built into a small form-factor PC and camera that can be attached to the different exhibits. The tech will watch and interpret the body poses of the people using the exhibit and how they’re standing or moving, but also what kind of facial expressions they’re pulling, for example are they laughing, focused, or excited.

To be able to make sense of what the camera sees we first need to train the technology, or rather for the technology to learn. We’ve built a temporary gaming booth fitted out with cameras in the Mixed Reality Lab, and the next step will be to invite people to visit and spend half an hour playing on an Xbox to capture the initial data that we need. Using this data we can build a model of measurable engagement that we can use to subsequently measure the engagement of visitors to the NVA.

But this is only half of the picture. The other work we’re doing is to figure out how to have a conversation with the player about the data that we’re capturing rather than just wholesale capturing everything, which most people would quite rightly think was overly intrusive. Each player is given a token that they can use to explicitly signal that they are engaging with the game, and which also acts as an access token to the data that is being captured. This token, and whether the player chooses to give it to someone else, or even gift it to the NVA, drives the conversation about data ownership. We’re exploring some lightweight NFC tags that can be easily integrated into a variety of form factors.

We’re having some interesting conversations with the NVA about what the servoken should look like, and prototyping possible ideas using additive manufacturing. It could look like a coin, inspired by the old coin operated arcade games, but then we don’t actually want players to lose their tokens inside a machine. Or it could look like Portal’s Companion Cube, where the material emancipation grill erases unwanted data about you when you leave the exhibition.

By Martin Flintham

Our workshop began with lunch followed by a short introduction from Elvira and Neil. They provided an overview of the Memory Machine project and addressed some myths about dementia. While it is a common perception that dementia is all about loss of memory, dementia affects everyone differently. Some people’s memory may not be affected, on the other hand, they may experience other physical and mental health problems. So we shouldn’t make assumptions that people with dementia will have poor memory. The positive side is that recalling memories can strengthen a person’s sense of identity, and this could help to cope with dementia symptoms.

Accordingly, our project aims to capture not only personal memories but also essence, identity and the indiscernible. Rachel presented a display exploring different tools that help us ‘remember’ in different ways and told stories relating to some of the objects she had bought in, including a box of photos and letters, a drawing of her grandmother, an old Thunderbird Toy and an old 1950’s camera! She talked about some existing digital and online memory tools such as Facebook and Google and addressed how we manage the way social media triggers and presents us with ‘memories’.

Our first activity involved discussing the tools we use to remember things, why we use them, what was special or helpful about them and why do different tools make people feel differently about their memories?

We had been asked to bring along a keepsake that evoked positive memories to the workshop – something we would be happy to share with others and these started some interesting discussions – in particular around why remembering these particular memories are important for our well-being. Our table identified how people collect keepsakes in different ways – one person had ‘collections’ of toys, badges and musical instruments that they nurtured and which were a big part of their lives, whereas another person had keepsakes that were emotionally attached to home, childhood and the people in her life. Everyone agreed their objects produced memories or experiences of nostalgia.

We needed a short refreshment break before getting to task with trying to make a blueprint of what we thought a ‘Memory Machine’ would involve – how to present memories as part of a digital memory machine; would we want analogue memories, such as photographs or letters? What would we do with positive and the negative memories, how would we use these memories now and also in the future? It was a difficult task to think about how a memory machine might work as an actual physical object in terms of ‘inputs’ and ‘outputs’, however we had a go and some fascinating ‘blue sky’ models and designs were created. Not a bad output for what was a really enjoyable afternoon!