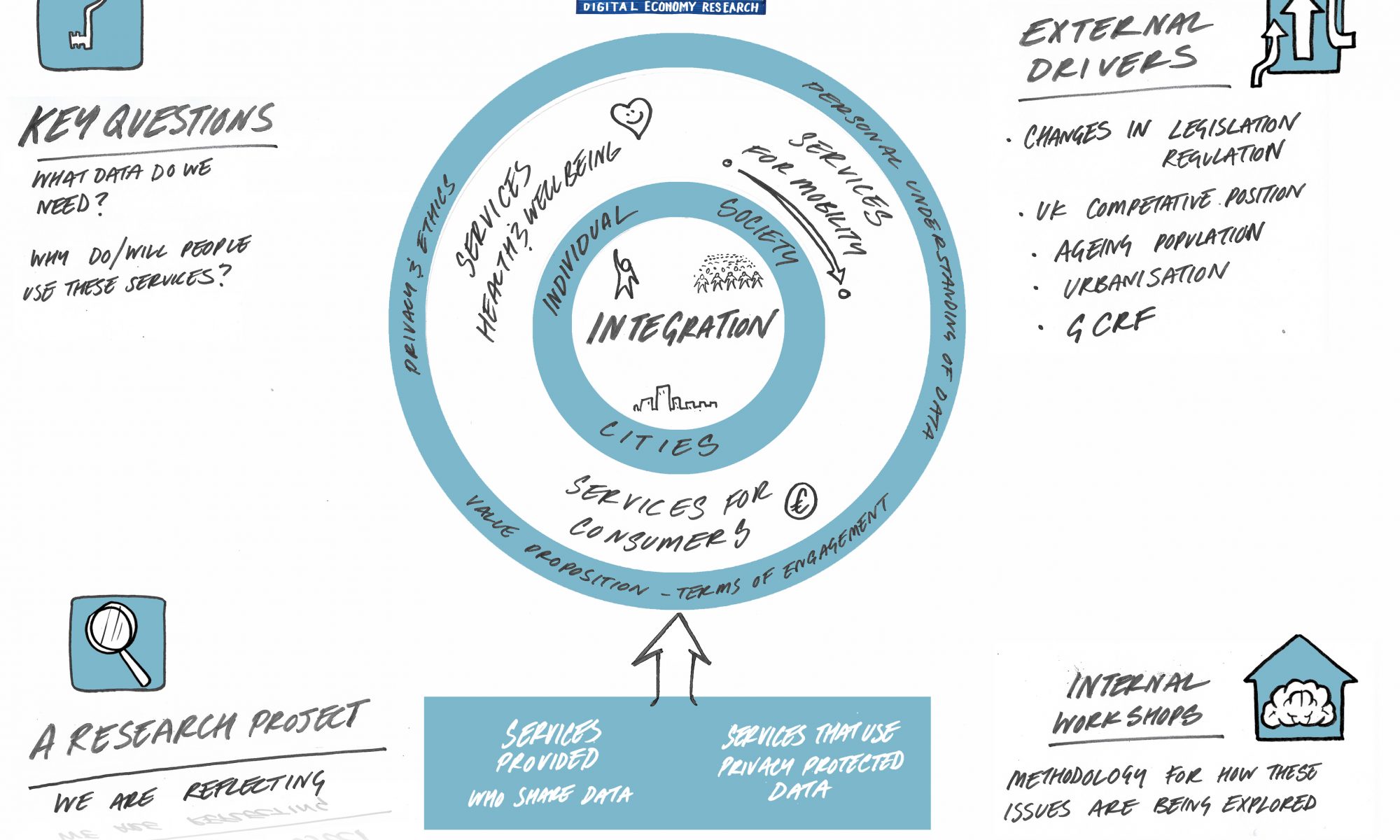

The overarching aim of our ‘Services Campaign’ was to gain a better understanding about the challenges faced by sharing our personal data with digital service providers. Working with our industry partners, we created different proof of concept digital services which acted as probes for us to study and investigate their impact on consumers, and the implications for privacy and trust.

We used a range of methodologies within these projects which included stakeholder workshops to enable co-creation of the digital services. We introduced our Moral-IT and Legal-IT ideation cards – tools developed by Horizon in earlier research – to facilitate reflection and discussion on ethical and legal issues within each of the projects – which helped us identify and embed safeguards into the new technologies. In addition, we also worked with internet users to gather and examine citizens’ thoughts and understanding about how their personal data is used.

The domains of application of digital services differed significantly, however the underpinning technical approach to delivering them had a number of similarities and consistent requirements. To support this we developed a software platform – Chronicle – which underpinned and supported each of the projects. Chronicle stored the digital representation of a timeline of a ‘thing’, the thing and the events on the timeline being defined by each project – for example memories in the Memory Machine project. In addition to the platform being customised and tailored to meet the requirements of each project, we also wanted answers to important questions such as: What did it mean to delete something from an historical record? Should deletion be possible, or should a record remain indelible? If so, what would be the implications for privacy and ownership rights?

The Services Campaign explored a range of services, each chosen to reflect the sharing of different types of personal data with diverse stakeholder groups:

Memory Machine (MeMa) focused on our sense of identity, and aimed to capture people’s identities through memories. The blending of personal and factual data provides an opportunity to shape how people wish to be remembered, while creating an afterlife legacy. Within the health and wellbeing domain we collaborated with the Institute of Mental Health and the Centre for Dementia. We worked with older adults, people with early symptoms of dementia, care home managers, historians and media experts, to seek to elicit personal stories and explored topics including privacy, consent, data security and ethics. We also addressed challenging issues such as painful memories, and events that may prefer to be forgotten.

In My Seat engaged with the public around use of their personal data with a view to improving their journey experience on public transport. We worked with bus users and stakeholders and explored the exchange of data between bus operators and travellers through the development of an app which provided dynamic, location-based, real time information. As well as practical information for bus users such as end-to-end route planning and live updates on the service, the app also provided location and profile-based notifications tailored to the current journey, which offered passengers the opportunity to learn about their local surroundings as well as their destination. The app chose content shared with the bus user – without it being necessary to include the operator as part of this information exchange. The intention was to include user-generated content from other travellers, but understandably the operators didn’t want information they had no control over associated with their service. This highlighted some of the challenges encountered when developing digital services and managing data use and distribution.

Panopticon produced a framework for tracking the interactions of people with products in public indoor environments, to create personalised ‘visitor experiences’ – meaningful to audiences, whilst at the same time providing venues with valuable information, to continually improve the experience and drive repeat visiting. We worked with the National Videogame Arcade (NVA) to capture video footage of visitors engaging with interactive exhibits and analysed the data with computer vision techniques to build measures of their emotional responses. This tracking of visitors’ movements and behaviours proved valuable to the curators of public spaces, however it yielded large amounts of unnecessary data which was very invasive. In order to address this, we combined the data with a physical token which was offered to visitors to use when engaging with interactive exhibits at the now rebranded National Videogame Museum (NVM). The tokens captured their movement and emotional responses and had the potential to be developed into digital souvenirs – however the important aspect being that visitors could voluntarily gift these back to the venue, thus allowing them to provide their consent to the venue to use their data. This enabled the NVM to analyse each individual’s experience, which provided them with a better understanding of the performance and appeal of their interactive exhibits.

Hybrid Gifting explored how physical products could be combined with digital media to produce novel hybrid gifts. The project aimed to enhance the experience of ‘giving’ and ‘receiving’ gifts and to support emerging gifting practices. As a result of working with Debbie Bryan, an independent creative retailer in Nottingham, we created a gifting app that enabled ‘givers’ to curate and share media as part of a physical gift. ‘Receivers’ of gifts open the digital content embedded within their gift via the app and are able to further personalise it by adding additional media – with access to the digital content being managed through the Horizon Chronicle platform. Work continues to examine what it means for people to associate personal content with a physical artefact as part of a sharing experience – in the manner of a closed privacy-preserving online interaction – and the value of hybrid gifts and their impact on the giver/receiver relationship.

The activities we introduced to better understand the use of personal data in each of the projects demonstrated the importance of privacy – particularly with regard to the context in which the data is shared. Whilst in one context sharing a particular type of data seemed reasonable, in another it was seen as invasive and alarming. The studies showed that users have complex ways of understanding their personal data. Our users came up with more than 20 distinct ways to describe their data, and there was a complex relationship between these descriptions – some was seen as personal but not necessarily sensitive or private, and when it had implications for other people (family members, friends), this affected how willing people were to share it. Operators and providers of services expressed concerns relating to the responsibilities involved in collecting and retaining users’ personal data, and ensuring compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Our activities highlighted the complexity of systems using personal data, such as the developer’s responsibility for system (mis)use and how a correct understanding of a system’s operation can be ensured. The need for human oversight, clear and transparent communication relating to privacy agreements, and how captured personal data would be stored, processed and used was highlighted as particularly important.

Our Services Campaign is now complete and we have introduced our Products Campaign – the third in the series, and developed in collaboration with the University of Nottingham’s Smart Products Beacon – nicely fusing our personal data agenda with the design manufacture and use of products. Please follow our Products Campaign Blog and the Smart Products Beacon website for further information.